Cookbooks find their materiality in a plate of food, but also in the transcendence of the meal: in its atmosphere, with whom it was shared, what conversations arose, and discussions regarding taste.

In this way its potential experiences clearly go beyond the book. The book is thus sustenance and nourishment. Through cookbooks personal stories are also widened, amplified, as they often speak to us from the situated knowledge of the person who writes and puts together the recipes. At the same time, that person is also resonating with a past, even if it is not evident, even if the book does not emphasize and commercialize that circumstance. Each cook explores known worlds that they have practiced, that are part of their own sphere, their bubble. Therefore, the cookbook has a flexible temporality, it can be talking about the present at the same time that it is talking about the past, with the hope that a diner, consumer or whomever reader will reinterpret the same recipe, and simultaneously it will also talk about a probable future. In this way the narrative of these books is both personal and collective. It is constructed from a solitude, that of the writer or of a team that made all the necessary preparations for a book, and it expands and spills through the re-interpretations of its readers. The genre of these books crosses many territories: narrative, instruction manual, chronicle. They cannot be confined in a container because the dynamics of their reading would spill out of its vessel. By nature cookbooks degenerate, as a form containing multitudes.

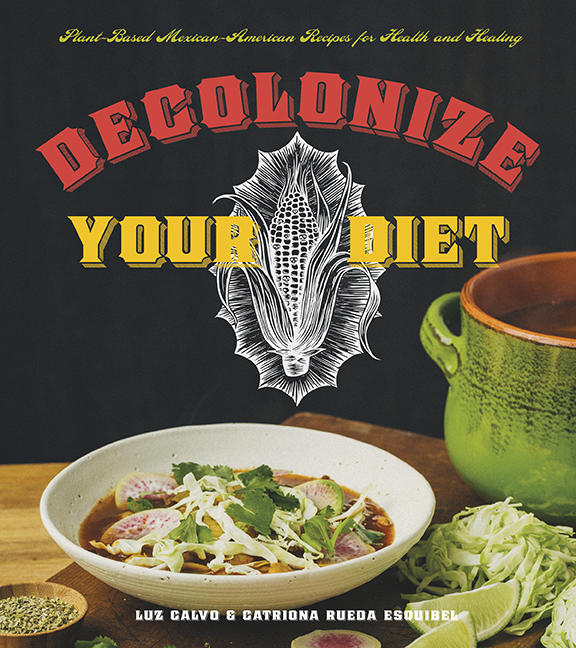

Another aspect that is foundational in the making of a cookbook is how the authors decide to approach the ingredients, which is the starting point of any recipe. As I see it, a cookbook can be many things: it could be understood as a stale touristic interpretation, or as a travel souvenir, for example. But because cookbooks revolve around eating — this being such a socially charged action— cookbooks bring with them an important political aspect. With this in mind I would like to briefly look at three publications that are fascinating examples and wonderful cookbooks in their own right. The books are Heirloom by Sara Owens, Mother Grains by Roxana Jullapat and Decolonize Your Diet by Luz Calvo and Catrió na Rueda Esquibel. In these three cookbooks I have found ways of seeing culinary worlds that understand cooking as forms of peaceful resistance, a way of doing activism from the trenches of our kitchens. And although these resistances are more subtle, it never ceases to amaze me how through these gestures, they somehow are able to mobilise something inside us that lends itself from its ordinary and domestic use, to seek sustainable changes that transform the way in which we understand ourselves within and with the world.

Heirloom by Sara Owens beautifully lays out how we can honor traditions that have nourished us for years, and teaches us how we can practice them in our daily life. Of course her interpretation of traditions is somewhat different than mine and probably yours,but there is some overlap in how we can approach food from a place where we are encouraged to really stop and think about how we treat our foods and care about food, so in turn it can also heal us. The book further explores health issues around food, without ever being oppressive and or posing restrictions. In its selection of recipes, arranged thematically by seasons, Sara Owens places great emphasis on soaking, sprouting, fermentation and the use of animal fats to improve aspects of your health while enriching and adding complexity to the flavors on your table. Let’ s not forget how beneficial fermentation is from a health perspective but also on a creative level, as it invites us to experiment with different ways of treating food and preserving it. Owens' peaceful resistance focuses on how her personal narrative and the intentions of her book gear us towards a more loving, kind and healthy society. And how this all stems from the realization that food can be not only one of the most delicious carnal experiences, but also a potent medicine for the body and spirit.

Narratives of how body and spirit intertwine, interestingly enough, are also present in the book Decolonize Your Diet, which introduces a difficult experience and important family event in which one of the authors, Luz Calvo, discusses her diagnosis with breast cancer and how it completely changed her relationship with food. From that moment on, during much of which she was unable to connect pleasure with food, little by little she and her partner Catriona began to establish a different bond with ingredients in their pantry and the ways they were prepared in the kitchen. Catriona comments that in Mexican healing traditions there is a condition called "susto" (fright), which disengages the spirit from the body. She says that one of the ways to cure this evil is to cover the person with earth, so that they can reconnect with the soil. This is how Luz started her road to recovery and began a treatment for the fright, for “el susto”, beginning with growing and tending their own garden, at the same time as they delved into the food of the indigenous peoples of what is now Mexico and Central America, in the full comprehension that their culinary practices have always been linked to stories about health and healing. And in speaking about health, they highlight issues, such as the cultural obsession with thinness, that has never had any foundation on what it means to be healthy. Decolonize Your Diet severely questions the ways which European colonial powers classify and stereotype indigenous populations as in need of education, religion or culture by a major cultural commodity, as of food and traditions. It is difficult to summarize the entirety of the project of this book but I would like to make reference to the importance of seeds. Seeds as cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation. Not only because studying this connects us to the environment in which we live, but also because knowledge about its spreading and abundance are political and fundamental to our livelihood.

This point brings me to Roxana Jullapat's book, Mother Grains. A visually stunning book in which she transports us to a world, our world, where grains are not only wheat, but could also be significant others, other multiplicities of our foundations, to the main options we have had for cooking, with other ancestral grains that could nourish our palate and the earth itself. The book is divided into the following grains: barley, buckwheat, corn, oats, rice, bye, sorghum and wheat, which according to Jullapat, can all be considered ancient grains.

There is an excerpt in which she describes the terms “ancient”, "heirloom", "artisan", "whole grain" that I think is important to discuss as Jullapat argues, since the terms are often used indiscriminately depending on the most catchy marketing angle of the moment. According to her, ancient grains are grains or pseudocereals unaltered by domestication; Heirloom or heritage grains are species maintained by gardeners and farmers, especially in specific regions or communities; artisan grains refer to the cultivation, harvesting and use of a grain variety; and whole grain products contain germ, endosperm and bran, unlike refined flour, which has had the germ and bran removed to extend its shelf life. I find it valuable that she stops to differentiate these terms that even I myself have used, I hope correctly. This book’ s intention, aside from offering recipes for wonderful bakes, is that we rethink the vitality of the ingredients we use when baking, which ultimately coincides with the accomplishment that Sara Owens as well as Luz Calvo and Catrióna Rueda Esquibel pursue. Not only to forage for ideas and knowledge in cultural and historical food traditions but to honor the present by looking to the past, to better understand ourselves from what is ever outside and feeds and heals us inside.

In a world of slings and arrows, with these authors I find continuous efforts to harvest resistance, from the kitchen and elsewhere, and tools to become the greates witches.

By Rebeca Pérez Gerónimo.

References:

- Luz Calvo, Catrióna Rueda Esquibel. Decolonize Your Diet, 2015. Arsenal Pulp Press.

- Roxana Jullapat. Mother Grains. Recipes for the Grain Revolution, 2021. W.W. Norton &

Company.

- Sarah C. Owens. Heirloom, 2019. Roost Books.